INL, UCSD Researchers Find Slow, Low-Energy Charging Of Li Batteries Creates Glassy Lithium; High-Performance Li-Metal Batteries

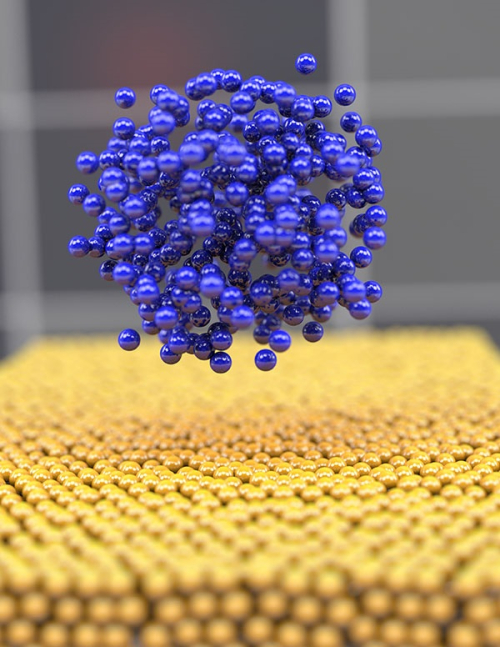

Scientists from Idaho National Laboratory and the University of California San Diego have shown that slow, low-energy charging causes lithium atoms to deposit on electrodes in a disorganized way that improves charging behavior. This noncrystalline, amorphous, “glassy” lithium had never been observed, and creating such amorphous metals has traditionally been extremely difficult.

The findings suggest strategies for fine-tuning recharging approaches to boost battery life and—intriguingly—for making glassy metals for other applications.

“Here, cryogenic transmission electron microscopy was used to reveal the evolving nanostructure of Li metal deposits at various transient states in the nucleation and growth process, in which a disorder–order phase transition was observed as a function of current density and deposition time. The atomic interaction over wide spatial and temporal scales was depicted by reactive molecular dynamics simulations to assist in understanding the kinetics. Compared to crystalline Li, glassy Li outperforms in electrochemical reversibility, and it has a desired structure for high-energy rechargeable Li batteries.Our findings correlate the crystallinity of the nuclei with the subsequent growth of the nanostructure and morphology, and provide strategies to control and shape the mesostructure of Li metal to achieve high performance in rechargeable Li batteries.” — Wang et al.

Lithium metal is a preferred anode for high-energy rechargeable batteries. Yet the recharging process (depositing lithium atoms onto the anode surface) is not well understood at the atomic level. The way lithium atoms deposit onto the anode can vary from one recharge cycle to the next, leading to erratic recharging and reduced battery life.

The INL/UC San Diego team wondered whether recharging patterns were influenced by the earliest congregation of the first few atoms, a process known as nucleation.

“That initial nucleation may affect your battery performance, safety and reliability.” – Gorakh Pawar, an INL staff scientist and one of the paper’s two lead authors

To discover how lithium atoms first come together during recharging, the researchers combined images and analyses from a powerful electron microscope with liquid-nitrogen cooling and computer modeling. This cryo-state electron microscopy approach allowed them to see the creation of lithium metal “embryos,” and the computer simulations helped explain what they saw.

Lithium, like other metals, typically exists in a structured crystalline phase. Such “grainy” lithium can lead to inconsistent recharging and shorts because crystals can grow in various shapes, Pawar said. Inconsistent lithium growth progression from one recharge cycle to another results in irregular shapes (aka dendrites) and can shorten battery life.

When the research team sought to understand the initial nucleation process, they were surprised to learn that certain conditions created a less structured form of lithium that was amorphous (like glass) rather than crystalline (like diamond).

“The power of cryogenic imaging to discover new phenomena in materials science is showcased in this work. It is true teamwork that enabled us to interpret the experimental data with confidence because the computational modeling helped decipher the complexity.” — Shirley Meng, who led UC San Diego’s cryo-microscopy work.

Pure amorphous elemental metals had never been observed before. They are extremely difficult to produce, and only a few metal mixtures (alloys) have been observed with a “glassy” configuration, which imparts powerful material properties.

“The glassy nature (that is, the absence of the ordered nanostructure, grain boundaries and crystal defects) of the Li metal avoids epitaxial growth and enables multi-dimensional growth into large grains, which is the desired form for a practical Li metal anode. The Li grains have higher density, lower porosity and tortuosity, less reactivity and better microstructure interconnec- tions than the dendrites. These features can substantially minimize the volume expansion, reduce the side reaction between Li and the electrolyte and maintain an effective electronic and ionic network or percolation pathway.As a consequence, a higher electrochemical reversibility would be expected for glassy Li. Therefore, from a structural perspective, glassy Li metal may be the key to solve the long-standing cyclability issue of using a Li metal electrode for high-energy rechargeable Li batteries.” — Wang et al.

The team also learned that a glassy lithium embryo is more likely to retain its amorphous structure throughout growth. The team found it could make amorphous metal in very mild conditions at a very slow charging rate, said Boryann Liaw, an INL directorate fellow and INL lead on the work. “It’s quite surprising.”

That outcome was counterintuitive because it was thought that slow deposition rates would allow the atoms to find their way into an ordered array—i.e., grainy lithium. To find glassy lithium under such conditions was considered unthinkable, Liaw said. Modeling work explained how reaction kinetics compete with crystallization to drive the glassy formation. The team confirmed those findings by creating glassy forms of four more reactive metals that are attractive for battery applications.

The research suggests how to better achieve glassy lithium deposits during recharging of high-energy batteries. When applied, the result could help meet the goals of the Battery500 consortium, a Department of Energy initiative that funded the research. The consortium aims to develop commercially viable electric vehicle batteries with a cell level specific energy of 500 Wh/kg.