South Korean billionaire Chey Tae-won said geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China have kept prices for electric car batteries higher for longer as his conglomerate looks to reduce its reliance on the world’s second-largest economy.

“Due to the geopolitics and the supply chain, the schedule has been changed,” Chey, the chairman of SK Group, said in a rare interview. “Without that, actually, I could have lowered down much more the cost of the battery side.”

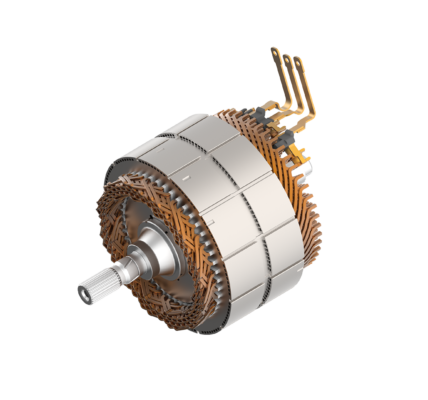

The Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act means the car industry cannot source materials from China if it wants to receive the full benefit from tax credits for EVs — even though key resources needed for their batteries are found in China. Batteries are expensive and account for around 40% of an electric car’s price tag.

SK’s electric battery unit SK On has been tapped by Washington to help the U.S. catch up with China in the electric car market. Along with Ford Motor Co., it’s received a conditional commitment for a $9.2 billion loan from the U.S. government to build three electric battery plants in America.

SK has been forced to look elsewhere for key materials and “cannot 100% rely on” China, Chey said.

“Everybody’s looking around at how we can actually make safe the supply chain,” he said. “Even my battery company recently visited Africa and South America to try to find some other options how we can get some supply from other options rather than China.”

‘The old days’

Negotiating varying regulations in different countries and regions has been difficult, compared to “the old days” when rules governing commerce were more consistent. “Right now, the market’s got a bit fragmented and each market has their own rules and their own regulations,” he said.

Workers tend to an unfinished Lordstown Motors Endurance electric pick-up truck on the assembly line at Foxconn’s electric vehicle production facility in Lordstown, Ohio, on Nov. 30.

Workers tend to an unfinished Lordstown Motors Endurance electric pick-up truck on the assembly line at Foxconn’s electric vehicle production facility in Lordstown, Ohio, on Nov. 30. | REUTERS

Chey, 62, was speaking in Paris, where he is helping to promote South Korea’s bid to host the World Expo in 2030 in Busan. Korea’s second-largest city is up against Riyadh and Rome, with the vote on Nov. 28.

SK Group’s operations range from batteries and chips to chemicals and telecoms. After Samsung, it’s South Korea’s second-largest chaebol — tightly controlled family-run conglomerates that have powered the country’s growth.

Chey said he welcomed confirmation that Washington had granted Korean semiconductor companies such as SK Hynix permission to continue shipping advanced chipmaking equipment to China. About 27% of SK Hynix’s revenue last year came from China, according to the company’s annual report.

“It’s good news, I’m happy to have that,” Chey, who has a net worth of $2.3 billion according to Bloomberg’s Billionaires Index, said. “Actually, our semiconductor reserve is the memory semiconductor so what I’m saying is it’s a kind of commodity. You don’t have to be strict on the commodity itself.”

On another potential flash point with China, SK Hynix is investigating how its memory chips ended up in Huawei Technologies Co.’s new smartphone after they were identified in a TechInsights teardown of the Mate 60 Pro for Bloomberg News. The company said it hadn’t done business with Huawei since the U.S. imposed sanctions on the Chinese company.

Chey said it was a “mystery” how Huawei secured the chips: “If we had our own distribution channel then we’re definitely not using that channel anymore, according to our internal investigations. It’s not our channels, but somebody else and somebody else is saying that I’m the end user.”

Broader semiconductor market conditions are “not good,” Chey said. “There’s an oversupply, and especially on the memory side.”

Shrinking returns

Shrinking the size of the chip is the main problem, he said, and returns are diminishing. “If you really want to have that advanced semiconductor we have to put in a lot of capital. Sometimes it doesn’t actually pay off,” he said. “Usually when you introduce a new technology, you can actually cost-cut more than 30% — these days, less than 10%.”

Amid the semiconductor industry’s sharp slowdown, SK Hynix reported an operating loss of 2.88 trillion won ($2.13 billion) in the latest quarter. Chey said chip cycles now last longer than previously but he hopes conditions improve next year.

Ahead of the World Expo vote, Chey highlighted how Korea’s key role in EVs and other technologies meant it could take a leading position uniting the world to tackle climate change. “There’s a lot of protectionism and geopolitics, but in order to get any kind of solution, especially for climate change, we need more global solidarity,” Chey said.

Some 25 years since taking over from his father Chey Jong-hyon, Chey Tae-won also revealed that he’s begun succession planning.

“I’m really thinking and I have to prepare that,” he said. “And if I have a certain type of accident then, well, who’s going to lead the whole group? I need some succession plan.”

He added: “I have my own plan but it’s not actually time to disclose yet.”