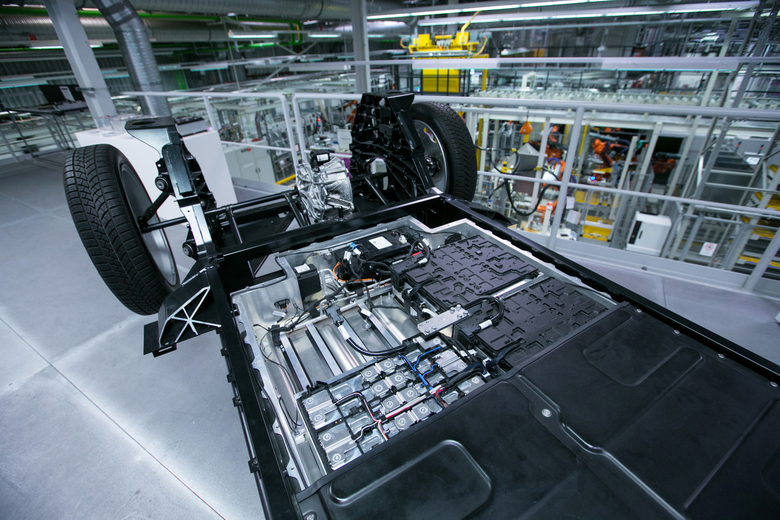

In a drab industrial zone of western Shanghai, amid factories that each year crank out hundreds of thousands of gasoline-powered cars, transmissions, and engines, the world’s largest automaker is racing to finish a new sort of plant, one that will produce a car unlike any it has made before. The 74-acre facility will have a newfangled assembly-line conveyor belt made of plastic instead of the typical steel or wood—a system that should be cheaper to reconfigure on the fly in order to manufacture cars whose shapes and layouts are likely to change more frequently and radically than any model the company has previously built. And the plant will be decked out with infrared cameras to monitor the safety of stockpiles of a component the company hasn’t before had to deal with in large volume: enormous batteries—each nearly as big as two coffins side by side—that have a nagging propensity to ignite.

What’s happening here in Shanghai is no incremental industrial tweak. It’s Volkswagen AG’s bet-the-corporation bid for supremacy in the electric-car age. “Volkswagen” translates as “the people’s car,” and for much of the eight decades of VW’s existence, the people were understood to be European or American and the cars to run on petroleum. But now VW’s biggest market is China, and the company, squeezed by new environmental mandates, has resolved to remake itself largely as a producer of electric vehicles, or EVs. Which makes this new Shanghai plant the forward base in the fight of VW’s life. When it starts producing electric vehicles next year, it will be VW’s “most modern factory worldwide,” says Fred Schulze, who heads production in Shanghai for VW’s joint venture in China with SAIC Motor, the Shanghai-based firm that is China’s biggest state-owned automaker. Schulze, a VW veteran, previously oversaw production of sport-utility and crossover vehicles from VW’s Audi unit—mostly gas-guzzlers such as the Q7 and Q8 but also the electric E-tron. From now on, Schulze says of VW, “our growth should be from EV cars.”

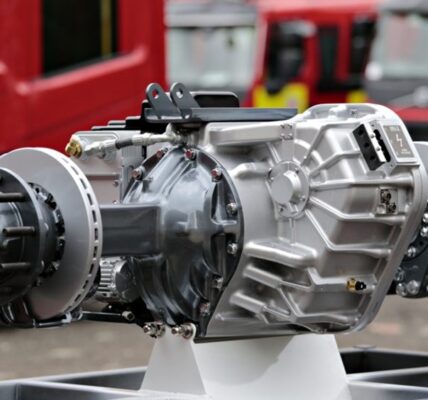

All across the global economy, titans of the fossil-fuel era are scrambling to adapt to an existential shift: the soaring economic viability of clean alternatives to dirty energy. Electricity and oil producers are struggling to ride—rather than be crushed by—a renewable-energy wave. Banks are trying to shore up their portfolios against losses induced by climate change. Automakers, though, are at a particularly scary fork in the road. The rise of electric vehicles—machines with multiple small motors instead of one big engine; with batteries instead of a fuel tank; with unprecedentedly extensive software systems instead of a transmission—is poised to redefine car making. If established automakers don’t adapt, and fast, the corporate infrastructure they have long seen as a signature asset may prove instead an insupportable stranded cost.

It’s far too soon to declare the end of the internal-combustion era. In the six months ended June 30, according to Wood Mackenzie, an energy-data firm, 97% of all new passenger cars sold globally had only an oil-burning engine under the hood. But it’s not too early to see that electric cars are coming on fast. Indeed, sales are shooting up beyond many supposed experts’ wildest projections. Globally, according to Wood Mackenzie, combined sales of passenger EVs—including full-electric vehicles, which have no combustion engine, and “plug-in hybrid-electric” vehicles, which augment their battery system with a combustion engine—jumped 47% from the first half of 2018 to the first half of 2019, to 1.1 million. The surge is being driven by a combination of factors: declining cost and improving technology, notably for batteries; increasingly convenient electric-charging infrastructure, particularly in large cities; and hefty government support.

Who wins and loses globally in the auto industry’s pivot to an electric-car future will depend largely on who triumphs in China. The country, home to notoriously polluted urban skies and a population gaga for SUVs, has become, in just the past few years, by far the biggest electric-car market in the world. Owing to a potent mix of government subsidies and mandates—policies driven both by local environmental concerns and by an intent to dominate a burgeoning global technology—China accounted for 54% of the world’s sales of plug-in-hybrid and full-electric cars in the year ended June 30, Wood Mackenzie says. The U.S. share: 16%.

But that’s just the start. China’s Society of Automotive Engineers has said 40% of passenger-vehicle sales in the country should be full electrics or plug-in hybrids by 2030. That’s not far off in an industry that plans in decade-long increments. To support the push, electric-car charging stations, some big enough to charge several hundred cars at a time, are popping up across major Chinese cities like so many Starbucks. Hundreds of firms in China are today manufacturing electric cars. A shakeout is probably in the offing, as China’s overall auto market softens and Beijing dials back the subsidies that have spurred the proliferation of EV startups. But the trend is clear: The country that trailed the world during the 20th century at developing cars that burn oil seems all but certain to lead it in the 21st in developing cars that hum on wired juice.

The result is an electric-car race in China that’s fast-paced, financially risky, and anyone’s to win. “It’s a little bit like the Gold Rush in California,” says Stephan Wöllenstein, the head of VW’s China business, who, as he offers this analysis, is sitting in an air-conditioned conference room, a box of VW-branded facial tissue on the table, on the top floor of the automaker’s tastefully appointed China headquarters tower in Beijing.

This summer, I spent some time in China with a few of the leading contenders in the electric-car race. They range from long-established Chinese auto brands to brash upstarts to well-capitalized Western companies like VW. There’s BYD, which according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance was the world’s largest maker of EVs for several years until Tesla recently overtook it—and in which Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway owns about an 8% stake. There’s Nio, a money-losing but technologically showy company that is producing gadget-laden electric SUVs. And then, of course, there’s Tesla, the California-based icon founded by the mercurial Elon Musk, whose pretty and pricey cars essentially created the global electric-vehicle market. Tesla, which declined to comment for this story, broke ground earlier this year on a colossal electric-car factory on the other side of Shanghai from the spot where VW is building its new plant.

To those in the U.S. and Europe inclined to fret about Chinese industrial hegemony, EVs represent the latest tech-centric industry that China has targeted to dominate. But this time China’s influence is likely to play out more subtly. Because cars are big and thus expensive to ship—unlike, say, mobile phones or solar panels—manufacturing them is likely to remain a largely local activity, with factories in major markets around the globe. But while China is unlikely to centralize the world’s electric-car manufacturing, it is defining how the global EV market develops—that is, setting the rules of the road. In many industries, Beijing has trailed Washington and Brussels. In the electric-car sector, Beijing, aided by some of the biggest Western multinationals, is leaving Washington and Brussels in the dust.

Industrial strategy in China is never the result of a single person. But, as much as anyone else, Ouyang Minggao is the technological father of China’s electric-car push. From his carpeted office on the top floor of an automotive institute at Tsinghua University, essentially China’s Harvard, Ouyang has spent more than a quarter century helping steer the largely government-funded research-and-development campaign that has resulted in today’s EV boom.

I meet Ouyang there on a sweltering Saturday morning. He’s running late, rushing from a session at which he helped strategize about further boosting the number of electric cars on the road in Beijing. His institute’s stairwells are lined with black-and-white photos of auto industry pioneers: Karl Benz, Rudolf Diesel, Henry Ford, Nikolaus Otto, and Meng Shaonong, who—a plaque below his photo notes—was “the founder of the Chinese automobile industry.”

When Ouyang came to Tsinghua in 1993, China had just launched an electric-vehicle R&D program. Over the years, spending rose. Then, in 2008, things got a lot more serious. That year, China showed off 500 domestically made electric cars and buses at the Beijing Olympics. More significantly: The global financial crisis hit. One direct result of the meltdown was the Obama administration’s 2009 economic-stimulus plan, which included billions of dollars in support for U.S. clean-energy industries.

That spending plan caught the attention of Beijing. And it led, in 2009, to what Ouyang describes as a “strategic discussion at high levels” in the Chinese government about how the country should proceed with its own clean-technology push. China’s State Council, the country’s top policymaking body, ultimately announced nine “strategic” industries, one of which was electric cars. Government subsidies began to flow in earnest and included hefty subsidies for battery makers, automakers, and electric-car buyers—with bigger awards to the companies that advanced technology most rapidly.

But China’s electric-car effort hasn’t just been about pushing tech boundaries. It also has involved manipulating consumer behavior. In big Chinese cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, municipal policies have severely constrained people’s ability to obtain license plates for combustion cars—but have made it easy for them to get plates for electric vehicles. China has also capitalized on several characteristics that Ouyang contends make it more suitable than the U.S. for large-scale electric-car use. China has relatively cheap electricity. It has a history of widespread electric-vehicle use, in the form of scooters. And, thanks largely to extensive state-sponsored high-speed rail for distant journeys, it has a consumer driving pattern that skews heavily toward short city trips, which are easier than long rides to build an infrastructure of car-charging stations around. For all these reasons, Ouyang says, “I think the United States is not the best application” for electric cars. “China is.”

If one city on the globe epitomizes an electric-car future, it’s Shenzhen. The reality jars me as soon as I exit the airport terminal on a steamy evening and, along with a few hundred other sweaty people, get in line for a taxi. Every cab in the queue, which stretches as far as I can see, is electric. What’s more, each is the same model: a hatchback made by Shenzhen-based BYD.

The growth of BYD—in Chinese, “bee-YA-dee”—epitomizes the dizzying speed with which China’s electric-car enterprise has matured from a geeky science project into a dead-serious industry. Founded in 1995, it early on was a contract maker of cell phone batteries for Western brands such as Nokia and Motorola. BYD went public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in 2002. It began selling combustion cars in 2003 and electric vehicles—taxis as well as buses—in 2010. Its early EVs were just modified versions of gas-powered cars. But around 2014, BYD’s R&D department began designing an all-new vehicle architecture—known in the auto business as a “platform”—in an effort to optimize the particular attributes of the electric vehicle by designing one from the ground up. Cars based on what BYD calls this “E-platform” began hitting the market last year.

BYD has benefited mightily from hometown government support. The agency that regulates Shenzhen’s taxis required that local taxi companies switch to EVs to maintain their permits to operate—and it doled out subsidies over the past few years totaling about $510 million to bring the price of each EV taxi down to that of a comparable combustion model, says Zeng Hao, deputy director at the agency. Today, all but about 100 of Shenzhen’s 21,000 taxis are electric cars—all built, naturally, by Shenzhen’s own BYD.

Anyone who assumes a Chinese electric car is a rattling econobox might want to take one of BYD’s new models for a spin. It lacks the it’s-good-to-be-king ride and feel of that crown jewel of the EV realm, the Tesla Model S. But it also lags the Model S’s China sticker price, which is upwards of $100,000. Loaded, the E-platform’s top model, the Tang, has a sticker price of about $51,000, after subsidies. A basic BYD model at the E-platform’s lower end can be had, after subsidies, for about $8,500.

The company’s leadership doesn’t appear overly worried about the new competition at home and from abroad. “We feel confident,” says Lian Yubo, BYD’s senior vice president for passenger-car R&D, noting that BYD has been at the EV game longer than essentially anyone. “We mastered all the skills by ourselves.”

One of those skills is the manufacturing of an obscure electronic switch, crucial to electric cars’ controls, called an insulated-gate bipolar transistor, or IGBT. Most automakers buy their IGBTs from parts suppliers. But surging demand for electric cars has created a market shortage of IGBTs. BYD isn’t constrained by that shortage; in the city of Ningbo, some 700 miles northeast of Shenzhen, it has its own IGBT factory, part of a unit known within the company as BYD Division 6.

As we speak, Lian teases me with word that, later that afternoon, BYD will announce something big. The news breaks a few hours later: BYD and Toyota will team up to build Toyota-branded electric cars that will hit the Chinese market by 2025. This is just the latest electric-vehicle deal BYD has struck with a foreign automaker; for the past five years, in a joint venture with Daimler AG, the German owner of Mercedes-Benz, BYD has been building electric cars sold in China under a brand called Denza.

BYD, though, isn’t content to be just the back-office builder of foreign brands’ Chinese EVs. It wants to become an aspirational global electric-car brand itself. That’s why, in 2016, Lian hired, from a VW-owned design studio in Italy, Wolfgang Egger, who previously had been design chief at Audi.

I meet Egger in his shiny new domain, the lobby showroom of a design studio that BYD built for him. Unlike Lian, who dresses plainly, Egger is all Euro style: He sports brown suede shoes, fashionably skinny blue chinos, a white dress shirt, and a well-cut windowpane sport coat whose blue hues accentuate his eyes. When I ask where he had it fitted, he flashes a grin and offers an of-course response: “Italy.”

Bolting VW for BYD was, Egger says, a no-brainer. “To create a future EV brand was, for me, very fascinating,” he says, adding: “A cherry was missing on my cake.” Since Egger arrived, BYD has moved to open a satellite design studio in Los Angeles, not far from Lancaster, Calif., where the company makes electric buses for the U.S., and it has expanded its global design staff from 120 to 200, with plans to enlarge it to 300. Among Egger’s top hires are the former head of exterior design for Ferrari and the former head of Mercedes-Benz’s Advanced Design Studio in Como, Italy. They came, he says, for the same reason he did: “You can have your playground like this as a designer to realize things and to influence the future.”

When Egger got to BYD, its cars had, he says, “a volume-brand design” devoid of “emotional feeling.” He hopes to create a global brand that “has a little bit, let’s say, German technology feeling, Italian sports car emotional feeling, and Chinese culture.” His key Chinese culture element is the dragon, a symbol of strength and good fortune. He has designed BYD’s new electric cars with myriad aesthetic nods to the dragon, particularly in their front. He hopes the headlights evoke a “dragon’s eyes,” the grille a “dragon’s mouth,” and the chrome or lighting accents between them a “dragon’s mustache.”

It all sounds a little dreamy—until Egger explains that this design wouldn’t be possible in a combustion car. The dragon’s eyes—the headlights—are visually accentuated in the BYD design because the hood slopes down to them steeply and tightly. That wouldn’t work in a car with an engine because the engine would require both a higher front profile and air-intake vents. At BYD, he says, “the combustion is the follower. The EV is the leader now.”

If BYD represents the Chinese electric-car industry’s establishment, Nio epitomizes the upstarts. The five-year-old company, which went public on the New York Stock Exchange last year, fashions itself as China’s homegrown Tesla. In at least one important sense, the price tags, that comparison is apt. Nio says it sells the most-expensive mass-production cars—electric or otherwise—built in China without the involvement of an automaker from outside the country. With all the options, its original and still most-expensive model, an SUV called the ES8, has a sticker price of about $76,400.

William Li, the Internet entrepreneur who founded Nio, has aimed essentially to out-Tesla Tesla at China cost. The premise: “We can sell the same performance but at half the price,” Charles Huang, the vice president in charge of developing Nio’s electric-drive systems, tells me one afternoon. We’re sitting in his office at Nio’s headquarters, an assortment of rented buildings in Anting, the same auto-making agglomeration of Shanghai in which VW is building its new electric-car plant. Nio’s conference rooms are named for Western cultural landmarks (“Eiffel Tower,” “Teatro Colón,” “The Guggenheim”). The headquarters’ café is decorated to resemble a chain of swank urban lounges that Nio has built for its car buyers in big cities across China. It serves up espresso from a $16,000 La Marzocco machine.

Nio even hired some former Tesla engineers, not surprising in an industry in which talent often moves to the highest bidder. But this year, Tesla launched Chinese sales of its Model 3, a car with a Chinese sticker price starting about $46,500. Suddenly Nio’s job got a lot harder. “Now our strategy has changed. We need to be more cost efficient,” says Huang, a University of Michigan Ph.D. who previously worked in Michigan developing a spacecraft that later went to Pluto and at SAIC, where he headed the electric-vehicle division.

Even amid the belt-tightening, Nio is charging ahead. A key to its strategy is a “battery-swap” system; for about $26, Nio buyers can roll their cars into small Nio sheds that now dot cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, watch their cars be hoisted on a lift, and, with the help of a proprietary machine that Nio engineers designed, have the battery unbolted from beneath the car and replaced with a fully charged one—if all goes well, in less than six minutes, or not much longer than it takes to fill a conventional car with gasoline. Nio is building not just a car but, it hopes, a network.

This business-model innovation is, I’m told, the brainchild of Li, Nio’s founder. I glimpse him behind a closed door in his glassed-in office in the Shanghai headquarters. But he won’t talk with me, the company says. One reason may be that Nio is bleeding money. The company reported a net loss of $391 million for the quarter ended March 31, a loss 71% greater than in the year-earlier quarter, and warned of a “challenging sales environment” because of declining subsidies, increasing competition, and a slowing Chinese auto market. Then, in June, Nio announced it was recalling 4,800 ES8 SUVs after fires broke out in the batteries of two that were parked. As the company proceeded with the recall, having decided “the battery has some problems,” fires erupted in two more ES8s, Huang says. No one was hurt, he says, and Nio replaced the batteries with a newer model. As of mid-August, Nio’s stock was trading at less than one-quarter the peak it reached around the company’s initial public offering last fall.

One response: fewer people. Huang tells me Nio’s total headcount, which in late 2018 reached a high of about 10,000, is now down to about 8,400 and will fall by this year’s third quarter to about 7,000.

But for all its financial shakiness—or perhaps because of all that spending—Nio makes an over-the-top electric car. One day I take a high-speed train about two-and-a-half hours west from Shanghai to Hefei, the city in which JAC Motors, a state-owned auto manufacturer, has built a new factory for Nio. In what amounts to a capital-light strategy for the startup, Nio designs the cars and pays JAC for every vehicle that JAC’s maroon-shirted workers roll off the line. The factory is architecturally striking, and it’s chock-full of European-designed robots. Outside, on the factory’s test track, I climb into an ES6, Nio’s just-released answer to Tesla’s Model 3, and floor it. The torque slams me into my seat back and squeezes out of me a whoop. Nio’s cars may be a drag for investors, but they’re a hoot to drive.

At least on the straightaway. On the road, with real-life twists and turns, a Nio’s handling can feel a bit squishy. “I think our drivability is quite good,” Huang says, “but we have room to improve.”

Raw numbers drive home the differences among China’s EV contenders. In 2018, tiny Nio sold 11,348 electric cars and posted a net loss of $1.4 billion. Bigger BYD sold 533,000 vehicles, nearly half of them partly or fully electric, and inked a profit of $413.2 million. Automotive granddaddy VW sold 10.8 million vehicles globally—only 79,000, or 0.7%, of them, partly or fully electric, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance—and it racked up a net profit of $14.3 billion. Stocks in all three companies have swooned from earlier this year.

VW was founded by the Nazis in the 1930s as a project to produce automobiles for the masses. But for all VW’s marketing of itself as a German automaker—“Das Auto,” thundered a company slogan—its center of gravity long ago began shifting to China. Working through joint ventures with state-owned Chinese manufacturers, the VW group now sells about 40% of its vehicles in China—more than in Germany, North America, and South America combined. It is China’s biggest automaker, wielding a market share there last year of 19%. Now—globally, but above all in China—VW is attempting to shift from builder merely of the people’s car to builder of the people’s electric car.

It essentially has no choice.

In Europe, its home market, the company faces two stark realities. The first is its own fault: In 2015, VW’s reputation was shattered by the revelation that its brass had, for years, knowingly built diesel cars that spewed excessive pollution, and then repeatedly lied about it to regulators. The second, which some at VW see as following from the first, comes in the form of a regulatory headlock from Brussels: a 2018 European Union requirement that automakers slash the carbon emissions of their car fleets 37.5% by 2030. VW, in the carbon wars, has an outsize target on its back: It coughs out fully 1% of global carbon emissions owing to the sheer number of cars it puts on the road.

In China, the company now faces another regulatory prod backing it into the electric-car corner. China’s central government, which for the past several years doled out billions in electric-car subsidies, is pulling back that support and implementing a mandate instead. In what amounts to a polluter’s tax, one modeled on a policy in California, China is requiring that automakers peddle a certain number of electric cars each year to offset their internal-combustion sales—or buy credits from greener rivals.

In short, the Chinese government is switching from a carrot to a stick. Wöllenstein, VW’s China head, predicts that, by decreeing more electric-car sales, Beijing will force economies of scale that, within a few years, will make electric cars less expensive than combustion cars to produce. “The lines will probably cross in 2022 or 2023,” he says.

If that happens, the Chinese government will have birthed a new global automotive era.

VW has been preparing for this shift since early 2016. That was when, in the immediate aftermath of the diesel scandal, the company realized it needed an alternative low-carbon technology that it could deploy at scale. VW had for a few years been manufacturing small numbers of electric versions of a couple of its combustion models, notably the E-Golf, a variant of its basic hatchback. But in 2016, VW started work on a new platform designed specifically for electric vehicles—the modular E-drive kit, or in German, Modularer E-Antriebs-Baukasten (MEB).

In 2018, the company announced an audacious new target: It will be carbon-neutral by 2050—not just in manufacturing its cars but also, far more significantly, in the operation of its cars over their lifetime on the road. VW executives are still trying to figure out how to meet this promise—how, for instance, to ensure that those who buy its electric cars charge them with clean, rather than dirty, electricity, particularly in China, where the power system is especially coal-dependent. At a minimum, though, the company will need to do something pretty radical: It will have to make the vast majority of its new-vehicle lineup electric.

It’s hard to overstate the epic nature of this shift. Which is why I went to Wolfsburg to meet the man directing it.

Thomas Ulbrich started at VW three decades ago as an auto mechanic. Today, with his shaved head and powerful build, he retains much of that factory-floor persona. But now he wears a blue suit and commands an office alongside other board members high up in Volkswagen’s executive tower. Ulbrich appears to operate at one speed. In a conventionally powered VW GTI, it would be sixth gear. Now, of course, Ulbrich drives an E-Golf, one he had the Wolfsburg paint shop coat in a particularly badass matte white. He lets me drive it; the interior smells of his favorite cigarillo brand, Clubmaster, and, when I press the power button, the speakers start pumping out “Cryin’,” by Aerosmith.

As we talk in his conference room, Ulbrich sheds his jacket, paces like a caged lion, and downs an espresso from a demitasse. Not long into our conversation, he lets loose a fact that takes me a good couple of seconds to process. Given the lead time required to design a new car, VW will begin developing, in the next few years, what will be its last-ever vehicle powered by an internal-combustion engine—in the lingo, an ICE. Ulbrich tells me he expects to have the following heart-to-heart with engineers who will lead that effort: “Gentlemen, do it good, do it right—do it really good and right—because it is the last time you are starting to develop an ICE platform.”

VW has recently let fly a flurry of statistics about its electric-car intentions, each brasher than the last. By next year, it will begin producing two cars on the MEB platform: a hatchback evocative of the Golf, called the ID.3, and a small SUV, the ID.Crozz. By 2022, it will be building MEB cars at eight factories: two in China, including the one in Shanghai; one in the U.S., in Chattanooga; and five in Europe. By 2023, it will have spent $33 billion on its electric-vehicle transition. By 2028, it will have sold a cumulative 22 million electric vehicles across 70 different models.

The first MEB production cars will start rolling off the assembly line in November. They will be built in a plant in eastern Germany’s Saxony region, an auto-manufacturing stronghold, in a picturesque town called Zwickau. I went for a look.

The Zwickau plant historically produced, every year, 300,000 Golfs, Golf Sportwagons, and Passats, along with about 10,000 auto bodies for Bentley and Lamborghini, luxury brands that VW owns. But, over the next two years, it will ramp down production of combustion cars—except for the Bentley and Lamborghini bodies—and ramp up production of electric vehicles.

VW is spending $1.3 billion to renovate the Zwickau factory for electric-car production. Some 40% of that money will go to the body shop. To protect the battery in a crash, the electric car’s body will be about 210 pounds heavier, in order to be stiffer, than a combustion car’s. The ID.3 will have about 6,000 welds instead of the Golf’s approximately 5,200.

Added welds aren’t the only headache. In a combustion car, the various electronic brains, known as electronic control units, or ECUs, work somewhat independently of one another. But in an electric car, in which the electronics are more fundamental to powering the vehicle, the ECUs are more closely linked. That means factory workers have to learn a new way of assembling them. And that’s why VW workers from factories around the world that soon will start producing MEB cars are parachuting into Zwickau to get up to speed.

One of the biggest contingents is coming from China. I meet one Shanghai worker, He Long, as I’m touring the Zwickau assembly line. He has worked for 24 years in the Shanghai factory complex run by the VW-SAIC joint venture. Soon he will go back to help implement MEB production there. I ask him how making an electric car will differ from making a conventional one. “Too many ECUs,” he says.

It will be crucial to VW’s global fortunes that He and his colleagues do a bang-up job cranking out the new electric models in China if Volkswagen wants to keep up with its Chinese rivals.

VW executives profess admiration for a handful of large Chinese electric-car makers, among them BYD. They say time will tell whether startups like Nio can make reliable cars. Wöllenstein, the VW China chief, suggests anyone attempting to drive a Nio a long distance be prepared to call the Chinese equivalent of an Uber: “Let’s say, keep your mobile phone and a DiDi app” ready. But VW clearly is eyeing Nio. When the head of the Zwickau plant shows me a presentation on VW’s electric-car push, it has Nio’s logo pasted alongside Tesla’s on a slide underscoring market competition. And Wöllenstein notes the gadget-laden cars from startups like Nio are an “indirect threat,” changing “customers’ perceptions of what is a must-have.” That competition is getting increasingly close. VW has inked a joint venture with JAC, the Chinese company that’s building Nio’s cars, under which VW and JAC will launch an entry-level electric-car brand aimed at young Chinese consumers. Its factory is to be built in Hefei, the same city that’s home to the Nio production plant.

Ulbrich, the electric-car chief, spent seven years working in China for VW—and in the process, developed a deep respect for the speed and sophistication of Chinese innovation. To this day, his office is decorated with Chinese art. He notes that many of his colleagues used to chuckle at the thought of Chinese electric-car makers outpacing the mighty German behemoth. But “the smile,” he says, “was for the first generation of these cars.” Ulbrich typically spends at least a few days each month in China, and he and his colleagues on the VW brand’s management board fly there twice yearly to drive the latest local competition. These days, when they assess their Chinese rivals, few in Wolfsburg are laughing.